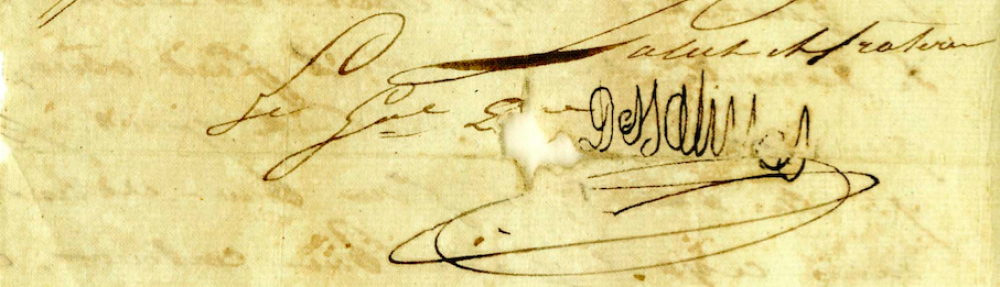

Jean-Jacques Dessalines to Victor Emmanuel Leclerc, 8 Fructior, an 10, MS Haiti 71-4, Boston Public Library. Continue reading

Dessalines Reader, 15 Febuary 1804

Jean-Jacques Dessalines, “Brevet,” 15 February 1804, MS Haiti 70-21, Boston Public Library. Continue reading

Dessalines Reader, 10 Prairial, an 10

Jean-Jacques Dessalines to Rochambeau, 10 Prairial, an 10, MS Haiti 67-8, Boston Public Library. Continue reading

Dessalines Reader, le 25 Floréal, an [unknown]

Jean-Jacques Dessalines to L.M. Desneiver[?], en chef a Jérémie, le 25 Floréal, an [unknown], National Library of Jamaica. Continue reading

Dessalines Reader, 23 Messidor, an 10

Jean-Jacques Dessalines to Donatien Rochambeau, 23 Messidor, an 10, MS Haiti 66-102 (10), Boston Public Library.

Haiti’s Revolutionary Calendar

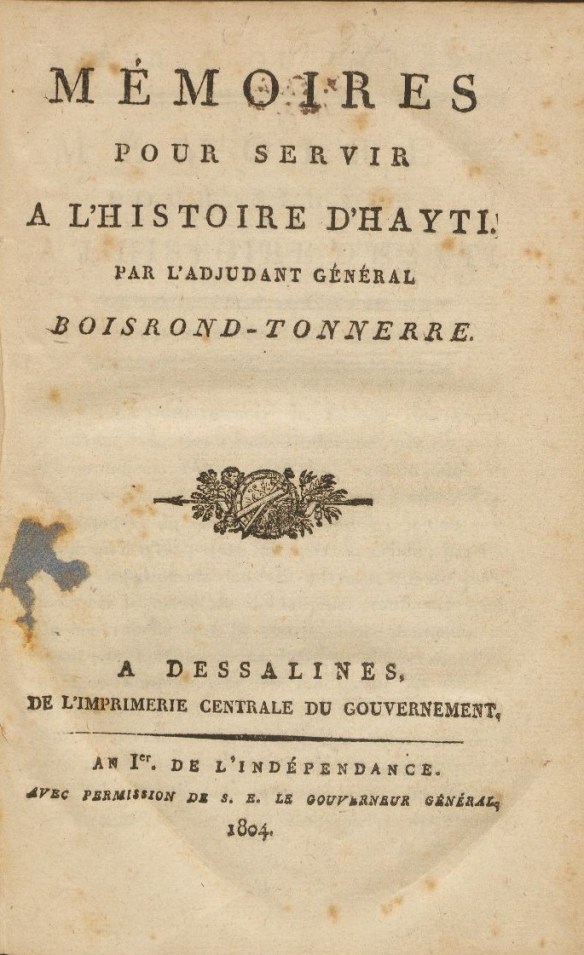

Prominently placed on the title page of Louis-Félix Boisrond-Tonnerre’s memoir is the following phrase: “An 1er de l’indépendance” (the first year of independence). The phrase is the first publication date to appear. It is only on the last line that the reader finds 1804, a helpful reference for those less familiar with Haiti’s independence chronology.

Boisrond-Tonnerre, Mémoires pour servir a l’histoire d’Hayti (Dessalines, 1804); digitized by Harvard University Library

Until recently, scholars relied upon a later edition of the memoir edited by Haitian historian Joseph Saint-Rémy that did not include the Haitian dating system of years of independence. Literary scholar Jean Jonassaint, who located the 1804 text in the Harvard University Library, notes that Boisrond-Tonnerre’s date placed the narrative within the revolutionary and official discourses of the era. Boisrond-Tonnerre was a secretary for Haiti’s first head of state, the former slave Jean-Jacques Dessalines. Months earlier, he composed Haiti’s founding document, the declaration of independence, which also included this new dating system.

Book Cover, Haitian Connections in the Atlantic World

My book, Haitian Connections in the Atlantic World: Recognition after Revolution will be out in October 2015! I am super excited and a lot of this has to do with the awesome cover designed by the marketing department at the UNC Press (with a little help from me!).

Jean-Jacques Dessalines (c. 1758-1806)

The following is an entry on Dessalines that I wrote for the Dictionary of Caribbean and Afro-Latin American Biography. I hope it’s helpful for anyone teaching the Revolution–comments, corrections, and additional information are most welcome!

Trading with Saint-Domingue will be Punished by Death

After the evacuation of the French troops from the western side of the island at the end of 1803, a small contingent of French soldiers, under the leadership of Jean-Louis Ferrand, fled to the city of Santo Domingo on the eastern side of the island. Since the evacuation agreement signed by the French general Donatien Rochambeau and the General-in-Chief of the Armée Indigène Jean-Jacques Dessalines did not explicitly state that the French relinquished control of the colony, Ferrand and his troops claimed to be the legal authorities for the entire island. Ferrand tried to convince foreign government representatives to prohibit trade with Haiti and enforced his own prohibition of trade with French and Spanish privateers. On February 5, 1805, he issued the Ordinance below that punished anyone caught trading with the “revolted of Saint-Domingue” with death. My research has shown–especially in the case of St. Thomas (a Danish colony) and Curaçao (a Dutch colony)–that governors were reluctant to support Ferrand’s prohibition on trade. Furthermore, even after they conceded and prohibited the trade, the prohibition was only loosely enforced.[1] This Ordinance, however, was publicized in both colonies and this copy is from the Danish National Archives.

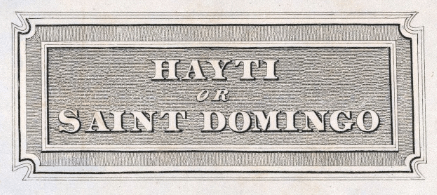

Hayti or St. Domingo/Saint-Domingue

The issue of naming in Haiti and the recognition or non-recognition of that name is something that I’ve been thinking about for a few years now. David Geggus wrote a great chapter called “The Naming of Haiti” in his book Haitian Revolutionary Studies. While undertaking my dissertation research, I was struck by the continued use of “Saint-Domingue” or “St. Domingo” by foreigners when they were referring to the territory that Jean-Jacques Dessalines and his generals had renamed “Hayti.” I wrote a short piece in the French journal Riveneuve Continents called “Identif[ying] the Island in its new situation”: The struggle for Hayti to overcome St. Domingo.” In this article I argued “Not only did the name ‘Hayti’ represent a break from France and a return to a time before colonialism, but the people assumed the roles of the rightful residents of the island. Natives; the land was theirs.” While I was a fellow at the John Carter Brown Library in 2013, I gave a talk and used map titles to illustrate the point that I was making about the uncertainty about Haiti’s status after 1804 and the resistance to fully recognize Haiti’s independence. The map titles that I studied suggest that international mapmakers were slow to adopt “Haiti” or “Hayti” as the name for the territory and only began to do so around the time that France officially recognized Haitian independence (1825). Even then, however, many maps continued to use the colonial name in addition to the new name.