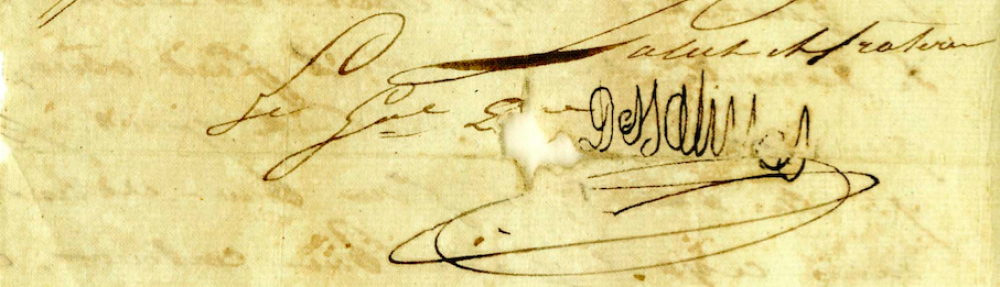

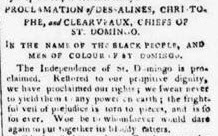

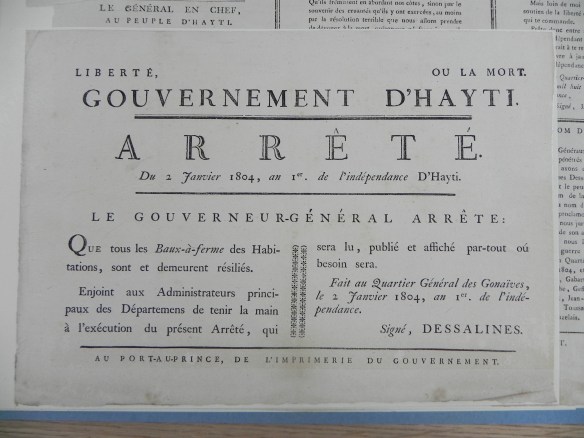

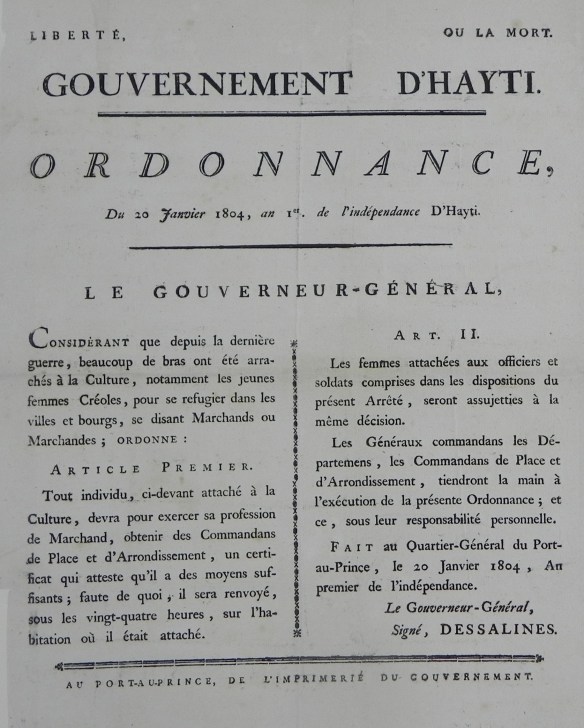

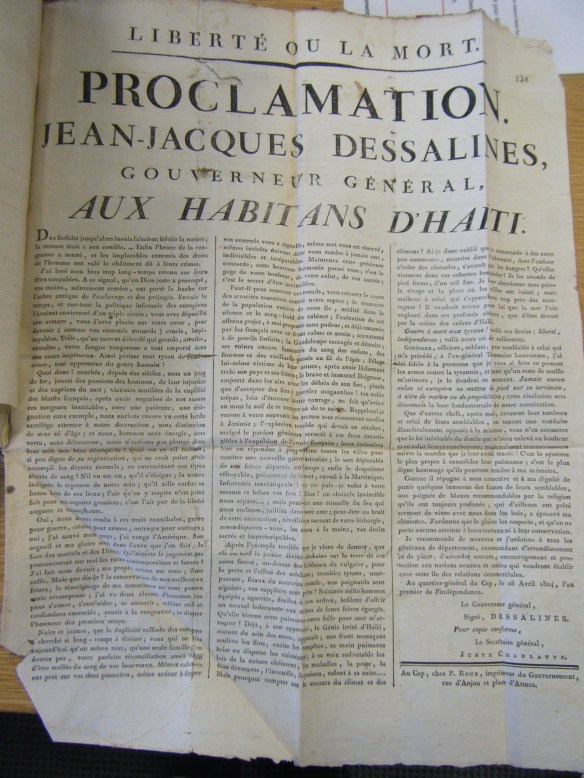

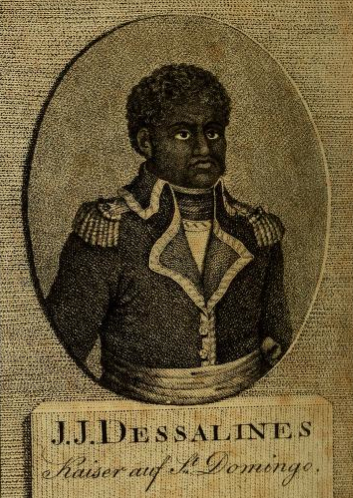

The surviving character descriptions and images of Jean-Jacques Dessalines differ drastically but most tend to portray him in a negative light. In recent years, however, a more complicated picture is beginning to emerge of Dessalines as a person, a military general, and a political leader. “Best known for his military brilliance and his violence against French planters in the wake of independence,” Laurent Dubois argues, “he deserves as much attention for his rhetorical and ideological interventions as well as his determined and skillful diplomatic negotiations with foreign powers.”[1] Foreign observers were not usually kind in their descriptions of him and they emphasized his alleged ferocity and his illiteracy. Deborah Jenson has recently argued that we need to rethink the claims that Dessalines was born in Saint-Domingue since the earliest first-person accounts all describe him as “Bossale” or “African.”[2] There is still a great deal to be learned about Dessalines and I am hopeful that Madison Smartt Bell’s forthcoming biography will help fill in some of the gaps.

Here, I am attempting to collect as many images of Dessalines as possible (and will arrange them in chronological order) to see if any kind of patter emerges. Please send images or links to images if you have them! (I am sure that there are more than the ones below – I couldn’t find source information for some of the images floating around online).

Dubroca, Leben des J.J. Dessalines, oder, Jacob’s des Ersten Kaysers von Hayti (St. Domingo), 1804. (German translation).